Second hand shopping has nothing to do with class - and everything to do with the environment

The youth no longer have their heads buried in the sand with the myth that more stuff equates to more wealth. With thousands abandoning the consumerism pushed by retailers on Valentine’s day and joining the climate strike yesterday, the question emerges whether protest is enough. And though it seems the change people are fighting for is systemic not individual, simultaneously young people are indeed a catalyst for change, in their own lifestyles and communities.

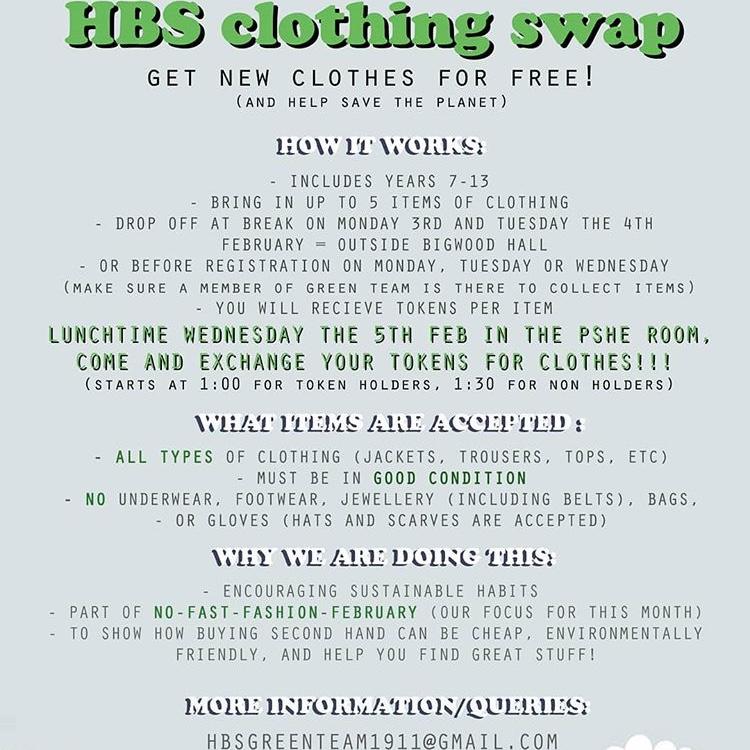

Last week, a group of young people known as the Green Team for The Henrietta Barnett School organised a clothing swap as part of No Fast Fashion February, the initiative of the month. This followed previous initiatives including designing reusable water bottles and bamboo cups, beach clean-ups, recycled crisp packet stations, and the annual switch-off fortnight. A spokesperson from the Green Team said that the idea originally arose from the Highgate Sustainability Conference last year where young people from across different schools came together to pool ideas and that the “damaging nature” of the Fast Fashion industry not only to the environment but to “human quality of life and workers’ rights” is something we all need to be aware of.

The role of the Green Team in general is to inspire students at school to take part in “good environmental practises” and to encourage personal choices with their wider impacts in mind. A huge take away from my conversation with a member of the team has been that reducing consumption is so much more important than reusal or recycling as the latter should really be used as a last resort and that we as consumers should be aware of the impact of our often unnecessary purchases. Fossil fuel-rich lifestyles are generally more common in the West, whereas its consequences are far reaching and international so it is arguably the disconnect between the two that means so many people are unable to associate their purchases with real climate impacts.

However, the premise for climate justice seems to be that although awareness is being raised and change is being fought for by young people, response from lawmakers is coming at an unbelievably slow rate for the magnitude of the problem. The current government is on its way to delivering laws said to make the UK sustainable but it seems that many of these are gimmicky and difficult to understand. For example, the pledge to stop supporting coal industries overseas - after having exhausted our own coal following the industrial revolution. Now rarely reliant on coal ourselves, the government has created the facade that we’re moving towards sustainability but fails to address that we already rely little on coal and that oil is our real problem.

Hopefully, in future, the government will use the example of young people at the Highgate Sustainability Conference to work towards something with more action than the Paris Climate Agreement and align their measures with their pledges, for example, by sticking to such agreements. Although the government has been painfully slow to respond to cries for climate justice, this is a problem that isn’t going away and that young people are continuing to fight for.

by Tahmina Sayfi