Flames of resistance in Colonial India. Veda Dharwar, Lady Eleanor Holles

He was an imperial policeman, forced to arrest Indian freedom fighters in service to his profession; she would hide those same prisoners who were vying for their independence, feeding them, clothing them, and ultimately arranging their escapes. The incredible predicament of this couple, living under the ‘British raj’ in the years preceding Independence, is a family history, passed down through the oral tradition, and only recounted to me last week by local resident Ajith Dharwar, the story of my great-great grandparents.

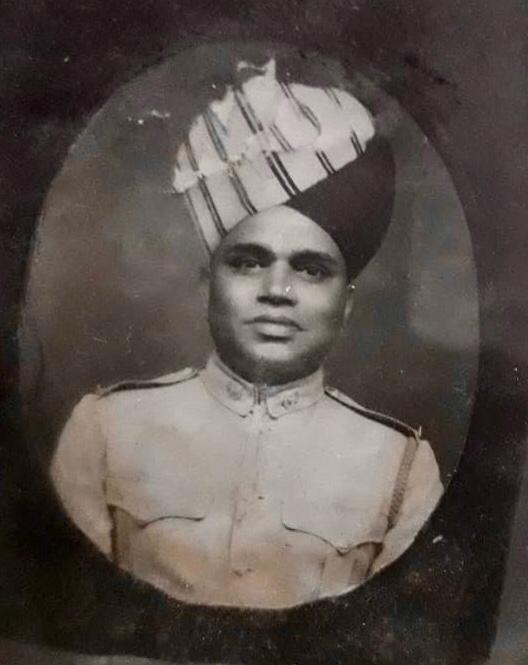

It is important to note that, due to the nature of memory, oral histories are considered to be less reliable than sources from the historical archive, and this of course shapes our perception of the historical narratives they present. Yet, they can also be an invaluable insight into gaining a more microcosmic understanding of the past. The Kingdom of Mysore, under which Govind Rao worked as a sub-inspector in the early 20th century, was a princely state in the south of India, created by the British East India company in 1799. The state was not ruled entirely under British hegemony as in some other parts of the subcontinent, there were agreements and alliances between the ruling Wodeyar dynasty and the British, with the implication that, although some internal autonomy was possible, British control still ran deep. Posted at the northern border of Mysore, Govind’s job was to quell unrest and demonstrations by the followers of Gandhi. Having been raised in a society where values of respect for the king were valued, and professions were essentially seen as a form of worship, Govind was bound to his job, and despite often sympathising with freedom fighters and agreeing with the fight for Indian independence, he was obliged to apprehend them.

Yet, the loyalties of Saroja, his wife, an incredibly brave and determined woman, lay in very different places. Ajith narrated how, ‘There was a train track on a bridge over the river. If the freedom fighters crossed over the bridge, they couldn’t be captured by the Mysore imperial guard as it was a different jurisdiction’. Therefore, Saroja would help the freedom fighters, plotting with her husband’s constables to organise hiding places for them, often within her own house. This was a calculated decision, as the house of the policeman would be one of the last places for the authorities to search. There, the freedom fighters would take refuge until Saroja could arrange their escape via the nearby bridge, into the next province.

As can be imagined, the conflicting loyalties within the household inevitably led to some secrets. Govind was aware of his wife’s decisions to help some of the prisoners, and indeed he too contributed to the growing resistance against British rule, secretly refusing to beat and physically abuse prisoners as he was ordered to do by his superiors. Yet, on some matters he remained in a state of blissful ignorance, and his wife did not inform him of her careful orchestrations of resistance. This was perhaps understandable, as the couple raised many children who, ultimately, needed to be provided for. Since the two were unfortunately unable to conceive themselves, the children had been entrusted to them by their siblings with the understanding that they would live better lives if they were raised by people with stable jobs. No matter how much his profession may have caused him moral dilemma, it was paramount that Govind keep his job.

Just under 10 years later, on the 15th of August, 1947, those flames of resistance engulfed the nation and India was finally granted its long sought after Independence. Ajith described to me the story his grandma, and my own great grandmother, had previously told him. He recalled that she described how ‘she was only 9 years old, and the family had recently moved to Bangalore. They turned on the radio to hear that India had won her independence, and those days are remembered first and foremost as a time of celebration’. However, with the bloody events of partition in the North and reunification in the South, troubles continued to brew on. That story of moral dilemma, of duty and of resistance is not limited to one couple nor one family. Many more such stories exist, and have, unfortunately, lost to the forces of time. Yet, that tradition of resistance, not invented under British rule, but strengthened by it, has continued to shape the history of my family, and indeed the country as a whole.