As it turned out, it wasn’t possible to travel across the world on a motor scooter. Instead, in 1966, Elizabeth Freeman waved goodbye to her family and Ilford home and set off on a two-year trip that would take her all the way to New Zealand, and back. Over fifty years ago, it was a different world that she saw. However, with travel now a foreign concept to most of us, it is a good moment to pause and reflect on the world that existed before Ryanair economy class and weekend getaways.

Throughout the 1950s, travel gradually opened up, becoming what is often known as ‘the golden age of air travel’. Elizabeth had been on a ‘package holiday’ to Switzerland as a child and had heard her dad talk about going to Baghdad in 1918. International travel had been seriously impacted by the Second World War, but this had also led to the rise in air travel, as planes became more common and more mass produced. She’d also heard of people ‘working their passage’ on boats, but it didn’t seem to be possible anymore. However, young people (plenty of them hippies) had taken to travelling to Nepal in Jeeps, and exploring Buddhism (or, as she later discovered, many were really trafficking drugs). Either way, Elizabeth wanted to see how people in other countries lived, and had in mind to take her Lambretta, a motor scooter, across Europe, into Asia, and ‘as far away as possible’.

Her parents were sceptical, and slightly concerned, but nevertheless, she wrote to the AA asking for a route. They told her it was not possible. There were no roads in the desert. Heedless, she headed to the biggest travel agent in London. They confirmed what she’d already been told. It didn’t seem likely that she’d travel the world on a motor scooter.

This was in August 1966, and she was twenty-five years old. It was soon after this setback that Elizabeth came across a coach advertising trips ‘overland to India’. They had one seat left, and she booked it. The trip would start in September.

The rest of the month was a flurry of packing and goodbyes. ‘It was very rushed, very exciting,’ she remembers. It was the perfect solution. She wanted to go as far as possible, but not to Africa (she’d heard missionaries talk about tropical diseases she didn’t want to contract) and had no interest in America. Her eventual target was Australia, and then New Zealand.

The bus journey took nine weeks. There was supposedly air conditioning, but it never worked. They travelled across all sorts of terrain in all sorts of weather in the bus, stopping each night to find accommodation, and every four days, to do some sightseeing and some washing. The passengers, ranging from eighty-four to around her age, became a community, and the younger (cash-strapped) ones would work together to secure cheap accommodation. It had to be cheap - in those days you were only allowed to leave the country with £100. ‘It didn’t matter if you were a millionaire,’ she says, ‘you couldn’t take it out of the country’.

Elizabeth’s favourite place, she says, was the dessert. It was quiet, peaceful and like the sea - just with sand as far as the eye could see instead of water. She saw a lot - another highlight was the ‘beautiful mosques in Iran’. However, she had to ration her camera films, and eked them out to three shots a day.

Eventually the bus terminated in Bombay (now Mumbai). This was where the group of travellers said goodbye, going on their separate ways, passports and suitcases in hand.

Already the trip had been eventful (while sightseeing in Baghdad, she and another girl had almost been kidnapped and taken to a brothel) but this is where Elizabeth would go it alone. Strong-willed (and maybe naive!) she ignored warnings that it would not be safe and spent three weeks travelling in countries she’d never been to, surrounded by languages she didn’t speak, and all before mobile phones and the internet existed. She travelled alone around Asia for three weeks, before arriving in her destination of Sydney via Cargo plane - almost like today’s economy class!

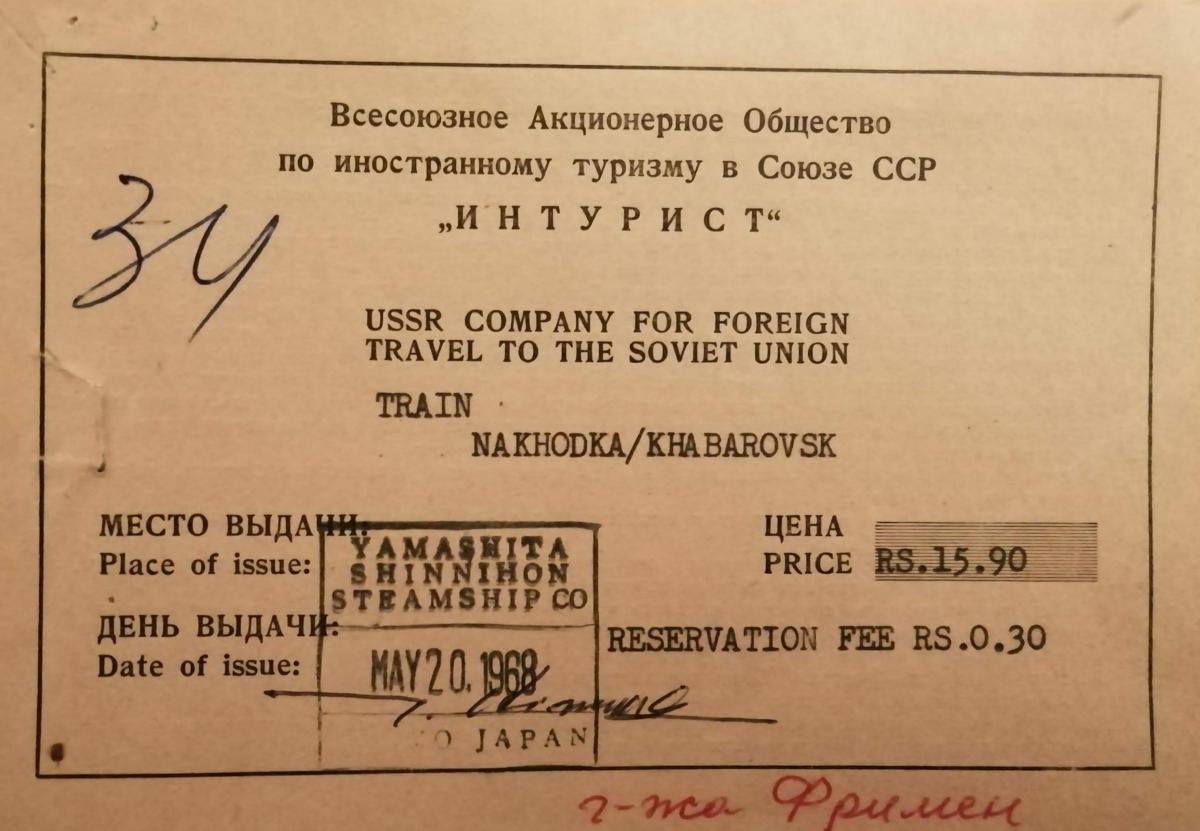

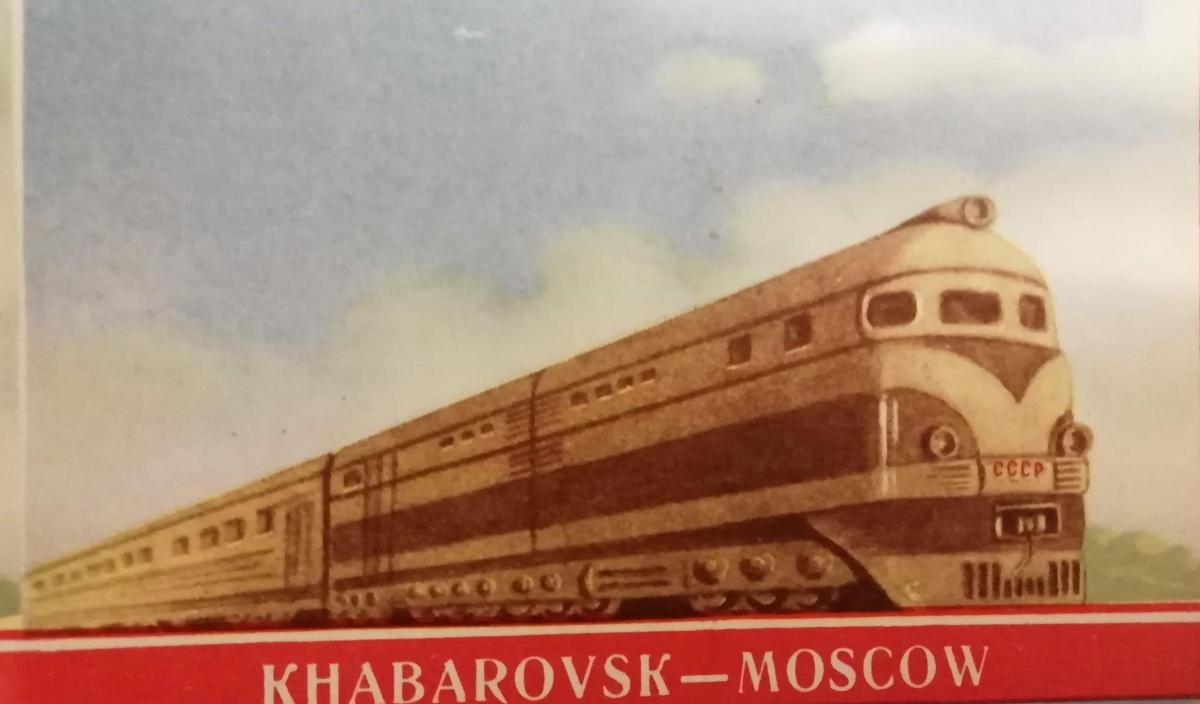

In Australia and New Zealand Elizabeth would work picking fruit for the money to come home and extend her trip to go to bible school. On her journey home, she’d travel round the Philippines, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Japan, before taking the Trans-Siberian Railway across the Communist Soviet Union.

Eventually she’d arrive home, two years after setting out on this journey around the world. She’d had time to think, experience the world, and now planned to become a teacher, struck by how important it was when she saw children learning in the street. She’d pursue this career, working in East London where she still lives today.

Travel itself has changed immensely since the 1960s. However, it still has a remarkable capacity for broadening the mind and enriching your world view and experience of life. Eventually, it should be possible once again, but crossing the world on a motor scooter might still be a challenge.