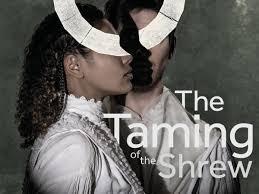

Before jumping in to the Globe’s current production of Shakespeare’s the Taming of the Shrew, it would be remiss to ignore the charged context behind this play. Taming of the Shrew is one of Shakespeare’s comedies, and being written for an Elizabethan audience, often some of the references or jokes fall flat with contemporary viewers, and one of the now tone deaf threads of the play is the misogyny that follows the plot. The play charters the breaking of a woman’s spirit and making her subservient to her husband, the title is a direct reference to this, the “taming” of a woman regarded as ill-tempered, also known as a “shrew”. Of course then arises the issue, was Shakespeare making a tongue in cheek social commentary on the patriarchal system he lived and worked in, or was he seemingly just another Elizabethan misogynist, vocalising his inherent biases in the form of theatre? Both views have a basis in the play, but in truth, it doesn’t really matter - because depending on the production and director, the misogynistic elements of the script may be played up for comedic effect and even tragedy, thus breaking the women hating message that this play may have once carried.

However, sometimes the director of said production chooses not to address this misogyny, and instead focuses on other elements of the play. This is not to say that one must challenge the over-arching theme of the play, but when totally ignored or done badly, especially for contemporary audiences, it crafts a jarring and vile production of what may otherwise have been a fairly decent comedy. Such is the case for Maria Gaitanidi’s production in the Globe’s Sam Wanamaker Theatre.

The production is not devoid of positives, the stage craft for one. Designer Liam Bunster has constructed a set with much versatility, a raised platform leading to the upper gallery divides the space in two, and the plethora of ladders from which the cast nimbly climb across creates an almost acrobatic experience. The only complaint one may have about this, and this is not the fault of the designer, but rather the limitations of the Wanamaker Playhouse, is that one feels very claustrophobic, and if seated under the balcony, doesn’t get to see the actors above them, rather hearing the lines they are delivering. For most plays, even listening to the actors on stage may be somewhat exciting, and would allow an audience to judge the merit of an actor on their vocals, rather than elements of physical theatre, but alas, the delivery of most of the cast is as wooden as the Playhouse it’s self, an oak structure.

Additionally, the costume design are good. The cast are clothed in cropped unitards, tights and shirts of brown and gold, which under the lighting, consisting solely of candles (which the actors both light and extinguish - essentially being their own light operators), creates an aesthetic charm to the play.

Although, these are superficial successes, with the actual subject of the production being botched. Gaitanadi has chosen to barely play with the problematic elements of the play, instead bizarrely focusing heavily on the subtle elements of meta theatre that the play is less well remembered for, often overshadowed by Hamlet’s ‘play within a play’. The framing technique of the induction (an explanatory scene, summary or other text that stands outside and apart from the main action with the intent to comment on it, moralize about it or in the case of dumb show—to summarize the plot or underscore what is afoot ) is something Shakespeare would use far more successfully in the Danish Tragedy. The play begins with a cast being assembled by their director, who shrilly delivers her lines in what can only be labelled as confusing; the audience weren’t aware that it was a part of the play as the lights hadn’t gone down and the abruptness of it made it appear as if the actors were only setting up. Furthermore, prior to this scene, unlike most plays, the cast were just hanging out on the stage, not backstage. Which while possibly being an intentional attempt by the director to reduce the boundary between the performance and the audience, only incited far more confusion than is necessary for the cold-open.

This meta theatrical approach is seemingly mirrored in the methods of which the cast rehearsed. Rehearsals began without knowing which characters they were actually going to be cast as, only finding that out much closer to the performance, hence leaving them with far less time to comfortably reside in their roles. Although a seemingly interesting idea, and possibly an entertaining way for an actor to approach a production, this did not translate into solid performances. Instead the cast feel stiff, just attempting to recite their lines rather than giving the comedic delivery...that a comedy requires. Indeed - as the production continues until April, the actors might grow better into their roles.

The ‘play within a play’ seemingly doesn’t reoccur at the end, but sometimes rises in the middle, such as the cast placing hats on the audience, or approaching them asking whether they like the play, and then saying that there is still more of the horrid thing to go. This breaking of the third wall, while being a background facet to the Bard’s original, now serve as annoying intersections, as well as the cast being self-aware that they are in an awful production - it begs the question, what’s the point of an audience sitting in a cramped playhouse for 3 hours and 15 minute watching disillusioned actors give a below par, poorly paced recital of what could have been a thought provoking rendition of Shakespeare’s most problematic plays?

That being said, for all we lionise Shakespeare, as is the case with theatre, and especially in the Elizabethan era, some productions were good, and some were not. And although failing, the premise behind this production as a theatrical experiment is an interesting one, and given more time could have worked better - which who’s to say that it won’t find its footing before the end of the run in April. Regardless, a visit to the iconic Globe is always a great experience, “all the world’s a stage”.