Minorities feeling isolated from media and press coverage in a 'world sinking into judgemental extremism' have come together to be in the spotlight.

Different religious communities anxious about being “unrepresented” packed a seminar at Hampstead’s JW3 Jewish centre to hear the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury and other faith leaders on how to redress the imbalance.

But what made it special was that professional mainstream journalists themselves were behind the move to bring the nation together.

The seminar was set up by the Religion Media Centre, an independent organisation aiming to increase understanding between those pushing the pen or holding the mic and those reading or listening to them.

Its volunteers include some retired from the BBC wanting to correct those perceived imbalances from past decades in the face of diminishing religious programmes on local radio up and down the country, perhaps mirroring a decline in church attendance by a third in the past 10 years.

Leo Devine was a broadcaster for 35 years who hosted a weekly religious show on local radio.

“There is a trend for being global nowadays,” he said. “But people still want to know what’s going on in their town, their city or in their community. It’s important we have honest and unbiased journalism that holds local councillors and others to account.”

He is now semi-retired but continues “living and breathing localism and journalism” at the Religion Media Centre off Tottenham Court Road and was invited to join a panel.

Journalists from the world of print took part in a discussion on reporting religion, from the Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Sikh press, explaining how communities can get their voices heard.

They were brought together by the media centre that helps journalists report on religion at a time when “society is deeply divided, with social media fuelling division and hatred encouraged by extreme ideologies”.

The centre offers no editorial line other than “religion matters” — even in a society witnessing faith in decline.

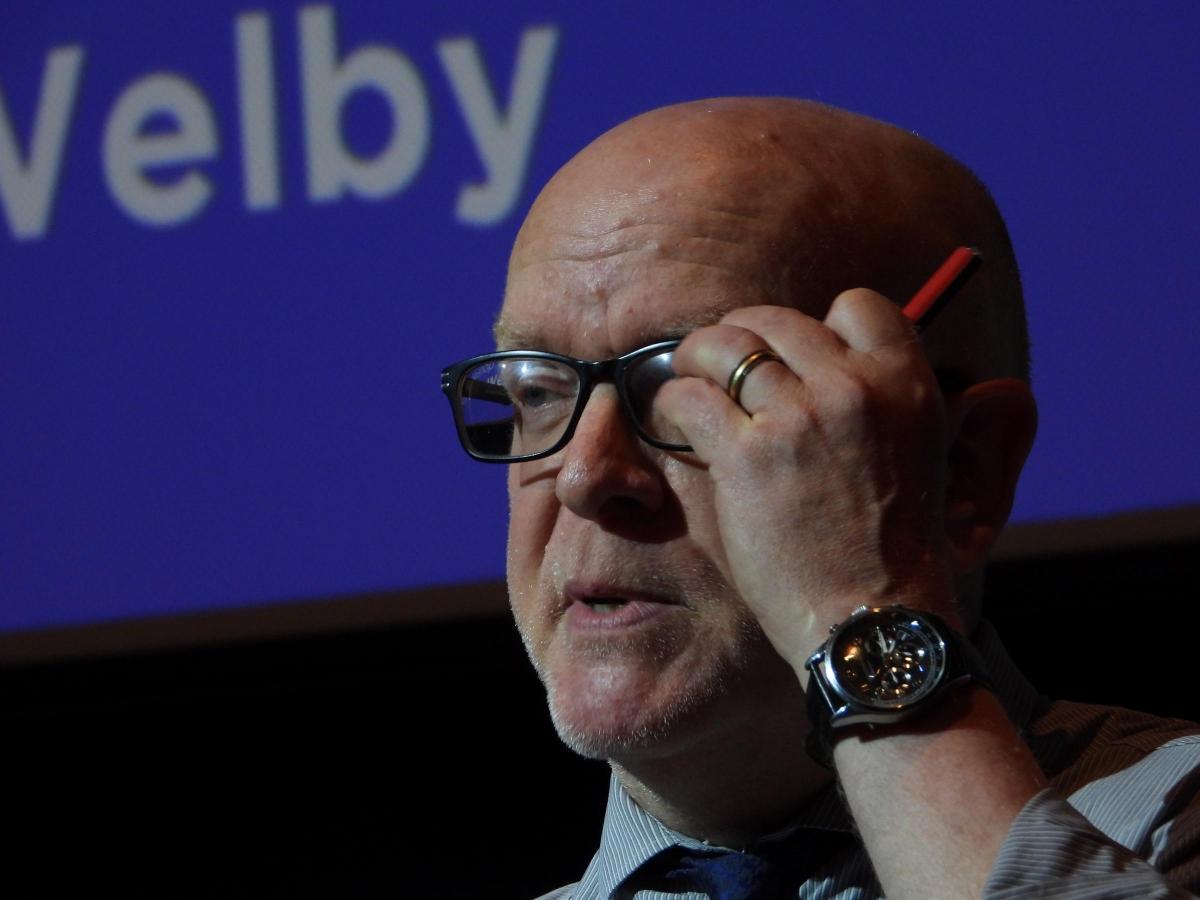

Archbishop Justin Welby himself acknowledged a world becoming more extreme and judgemental, fuelled by social media and how today’s journalism gets really personal.

“Good stories hang around people,” Welby told the seminar. “Stories that hang on a ‘concept’ are difficult and don’t work well on TV. You need a picture of a person, preferably looking slightly harassed or tearful, getting into a car and driven away at speed.”

The mood the seminar heard about was the ‘breaking news’ ethos the Archbishop feels often leads to reporting out of context.

“There is an absence of forgiveness and possibility redemption,” he said. “People are treated as though they were the worst villain on earth.

“But where do you then go when terrible things happen? If you treat people as the absolute final evil, how do you deal with issues like civil war in Sudan?”

But the Archbishop is facing his own demons with his liberal views on gay marriages which rocked the Anglican bishops’ conference in Uganda in April that attacked his Anglican leadership.

It wasn’t exactly the Good News you get from The Bible, yet he is philosophical about it.

“I’m an historian,” he says. “You can’t work out my legacy until another 30 years when I’m pushing up the daisies.”

He was asked in the staged conversation with ITV’s Julie Etchingham about gay relationships being blessed by the church that seems to have caused a religious schism at the Uganda conference.

“It’s like asking why the Anglican chicken got run over,” he suggested. “Because it insisted on staying in the middle of the road.”

The bishops had challenged Welby’s Anglican leadership “until he repents”.

The seminar audience heard about the bishops’ conference, where Dr Foley Beach declared “with broken hearts, we can no longer recognise Archbishop Welby as the first among equals.”

Et Tu, Brute.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here