In the biggest ever exhibition of his portraits, David Hockney shares something of his life through the depictions of family, lovers and friends.

"What an artist is trying to do for people is bring them closer to something, because, of course, art is about sharing: you wouldn't be an artist unless you wanted to share an experience," Hockney said, by way of an introduction to the show.

This collection of more than 150 portraits spans 50 years of his career and is a journey through the preoccupations and techniques which have characterised each phase of his work.

Having rarely accepted commissions, Hockney's portraits are rather an insight into his personal relationships, while alongside portraits of his inner circle are also the faces of some of the greatest cultural figures of his time, including Andy Warhol, Freud and WH Auden.

From bold oil paintings to detailed camera lucida drawings and cubist-influenced photo collages, the gallery shows Hockney's versatility and skilled draughtsmanship as well as his quest to perfect the genre.

The artist recently asked: "How does one make an interesting portrait in the 21st century?" and the range of techniques he has explored is in clear pursuit of an answer.

The exhibition, organised chronologically, starts with Hockney's iconic double portraits of the late sixties and early seventies. Among them are the famous Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, which came fifth in the BBC's recent "Greatest Painting in Britain" poll as well as being a best seller in the Tate's post card shop.

This classic portrayal of marital tension shows Hockney's close friend Celia Birtwell standing apart with a despairing demeanour from her then husband Ossie Clark and their white cat. It is often cited as an example of the artist's profound intuition, substantiated by the fact that the couple went their separate ways shortly afterwards.

The dual portrait of Hockney's parents is another display of this ability to capture so much more than the physical appearance of his subjects. The father is sat hunched over a book while his mother, subservient, sits to one side observing her son.

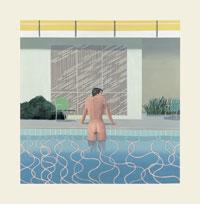

Also featured in these vibrant canvasses is Hockney's former lover Peter Schlesinger, most famously depicted bare-bottomed in Peter Getting Out of Nick's Pool (1966).

Schlesinger came into Hockney's life in Los Angeles in 1966 when the artist was studying at UCLA. He was for Hockney the embodiment of the Californian dream and his place in the gallery, representing the homo-erotic flamboyant lifestyle they enjoyed, stands in stark contrast to the working-class Bradford Methodists that were parents Laura and Kenneth Hockney.

Alongside these images of close friends and family are a series of self-portraits, which similarly track Hockney's artistic progress. However, ironically, towards the end of the exhibition we also begin to see something of his demise.

At the opening of the exhibition Hockney said that he always viewed his current work as his best, but it is hard to see his latest offerings as the pinnacle of his achievements.

Portraits After Ingres in a Uniform Style (1999-200) comprise a series of experiments with the camera lucida which are factually accurate but nevertheless lifeless portrayals of the guards at the National Gallery. Meanwhile the double portraits he painted last year are generally seen as his worst ever.

However, Hockney remains one of Bradford's - and Britain's - greatest artists and this exhibition has proved to be immensely, and justifiably, popular. So much so, that my one main gripe with it was having to fight my way through the sea of heads in front of me.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article